Chips of the Pentium D series were among the first CPUs on the x86-processor market, which, instead of the supposed monolithic, dual-core design, carried on board two single-core (although with Hyper Threading support – one core, two threads, but not all processors have the technology HT was active) of the Pentium 4 chip familiar at that time.

Back in 2005, the Pentium D series of processors for Intel was rather a forced measure, because the development of Core 2 Duo / Quad was at the final stage, but it was still far from release, nevertheless, the answer to the super successful chips of the competitor AMD Athlon 64 X2 had to be provided promptly. Thus, the “gluing” of two Pentium 4 appeared. This is how it was then dubbed by the specialized media.

Now in 2020, this is certainly not very believable, but AMD was far from being a pioneer in the modular arrangement of central processors – the first was Intel. And this is damn funny, because now it is Intel Corporation that protects the monolithic design of the CPU (talking about its amazing and undeniable advantages in games), and back in 2005 it produced the first mass x86-compatible chip (namely mass and x86, since for example at the same IBM multichip processors a dime a dozen) consisting of two chips called Pentium D.

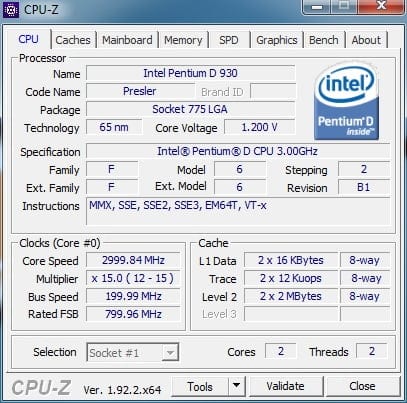

Of course, the subject from this material was by no means the first conditionally “chiplet” processor from Intel, nevertheless, Pentium D 930 belongs to the second generation of dual-crystal, dual-core processors from the blue giant.

Processor

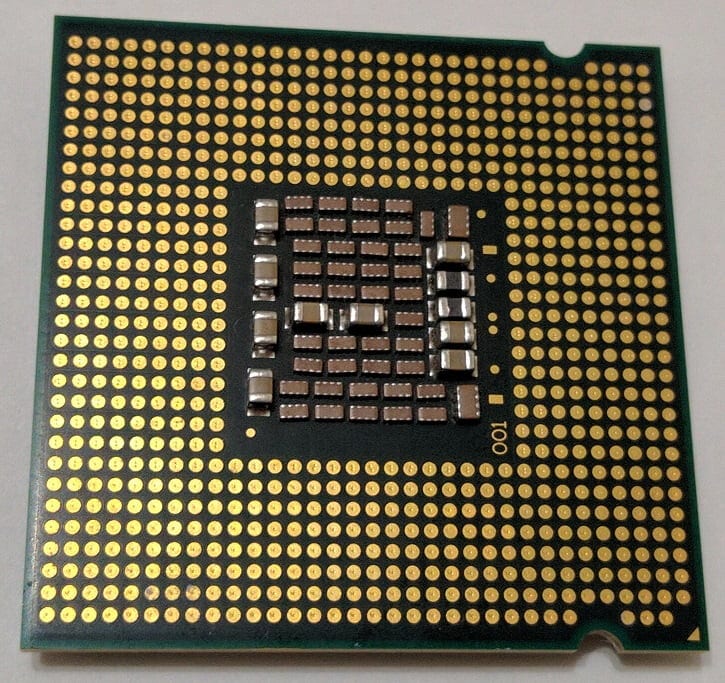

Unfortunately, due to the fact that my copy of the Pentium D 930 chip had a rather curved heat-distribution cap, back in 2011 it underwent a grinding of its base, after which its heating did not slightly decrease. However, for this reason, my sample now looks like this:

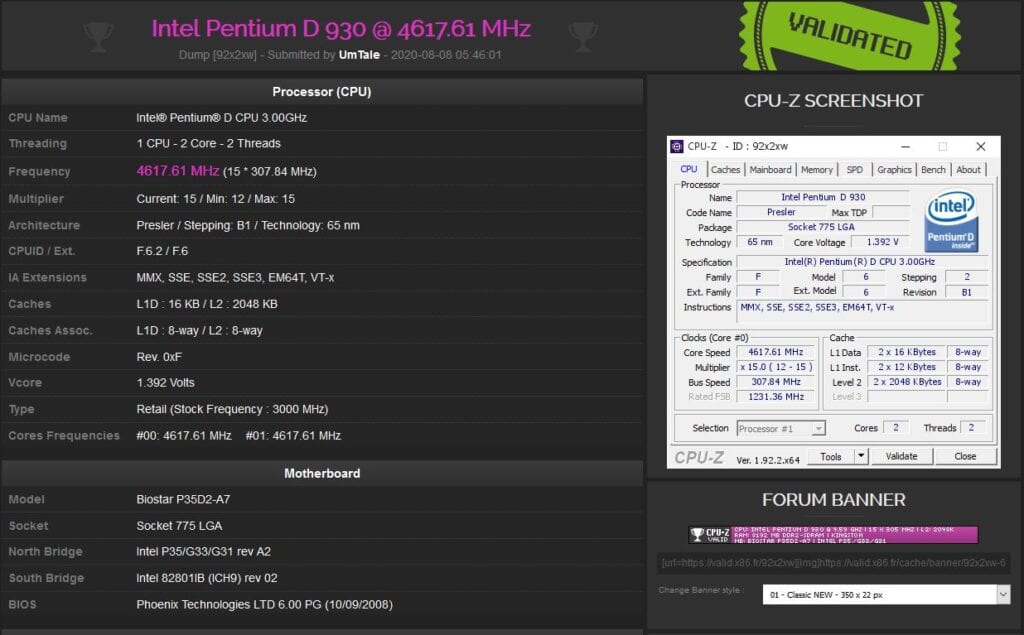

The Intel Pentium D 930 processor is based on two 65 nanometer Pentium 4 Cedar Mill crystals, belonging to the NetBurst long-pipe architecture. But due to the peculiarities of production, the chipmaker decided to give the resulting product a new codename Presler.

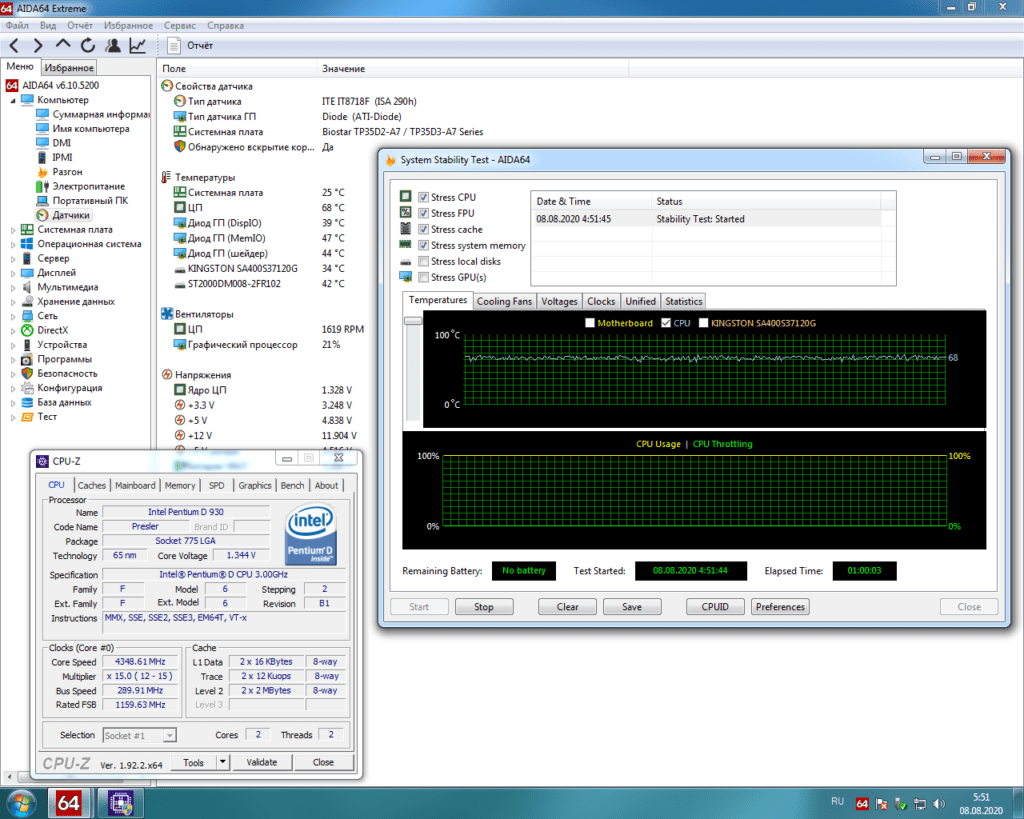

The tested CPU has 2 megabytes of L2 cache per core, operates at 3000 MHz (multiplier 15 and 200 MHz bus), and has a TDP of 95 watts. The base supply voltage of the cores is at around 1.260 volts (According to the monitoring of the motherboard. CPU-z somewhat underestimates the final results).

The chip is endowed with support for x86-64, SSE3, and VT-x instructions. However, it does not have the required extensions SSE4.1 and SSE4.2 at the moment.

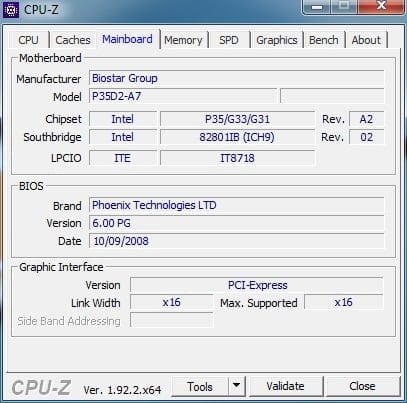

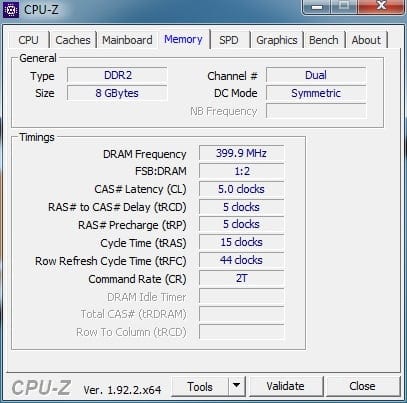

The CPU itself (as is customary now) does not support the specific type of RAM, or the speed of RAM, because in those “bearded” times, the “north-bridge” was responsible for this. Our test board uses the P35 chipset, which supports both DDR2 and DDR3 up to 1333MHz. However, the board itself has only DDR2 wiring. Accordingly, in our case, in base mode, the chip started up with RAM at 800 MHz and delays of 5-5-5-15.

Test setup

- Motherboard — Biostar P35D2-A7 with modified BIOS from TP35D2-A7

- Processor — Pentium D 930 (rev. B1)

- CPU Cooling — Cooler Master Hyper 212 EVO

- RAM — 4 x 2GB Kingston (99U5429-007.A00LF 34CC2E04) with a total volume of 8GB

- Video card — Gigabyte Radeon HD 5870 1GB GDDR5 850/4800MHz (GV-R587OC-1GD)

- Storage — KINGSTON 120GB SA400S37120G

- Power supply — Chieftec GPS-1250C

- OS — Windows 7

Pentium D 930 overclocking

To begin with, I tried to find out at what frequencies the Pentium D 930 will be able to operate stably at the base voltage. It took me literally an hour and a half to complete this study – the test chip was able to obey 3945 MHz at a stock voltage of 1.260 volts. Not the best result, but this is not surprising, because in the past this specimen has been exposed to frequent overheating and most likely degraded.

Then I decided to slightly raise the voltage to 1.320 volts and thus I was able to pass an hour stress test at a frequency of 4125 MHz. But, frankly, these were only sighting attempts. My main goal was to get the 65nm monster to function stably at 4500MHz, and considering that it was able to pass the stress test at 4125MHz at 1.320 volts, I had a pretty good chance. But alas, having set 300 MHz on the bus and 1.450 volts vCore, I could not pass even 10 minutes of the stress test in AIDA64.

Unfortunately, although the motherboard was able to raise the voltage up to 1.750 volts, its power phases gave up already at the level of 1.460 volts. Thus, I had to reduce the voltage, and with it the FSB frequency.

The result of a stable frequency in this bench-session was 4350 MHz at a voltage of 1.348 volts. Moreover, it should be noted that without additional blowing of the processor power circuit, it was not possible to pass the stress test at this frequency and with such a voltage. Remember this if you want to repeat my experiment.

The step-by-step overclocking table is below:

| Frequency FSB (MHz) | 263 | 275 | 290 | 300 | 308 |

| Final processor frequency (MHz) | 3945 | 4125 | 4350 | 4500 | 4617 |

| Processor supply voltage (Volts) | 1.260 | 1.320 | 1.348 | 1.450 | 1.492 |

| Peak temperature with load (℃) | 61 | 67 | 72 | ~83 | ~88 |

| Successful pass of AIDA64 stress test | + | + | + | – | – |

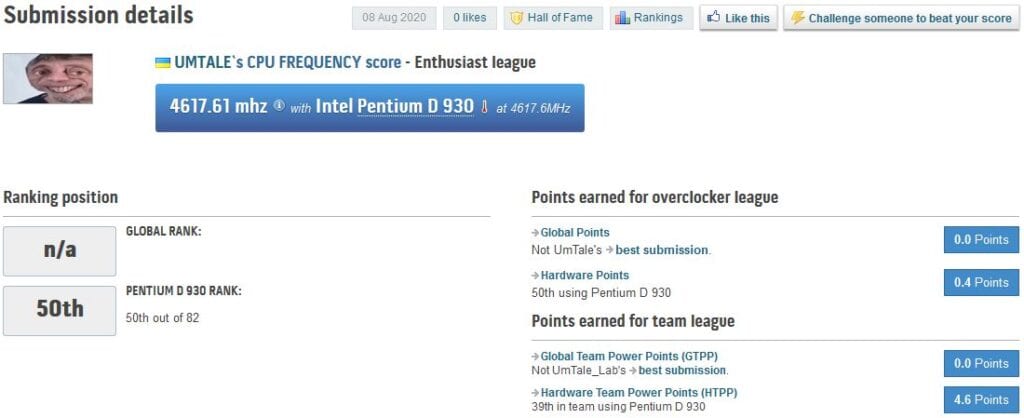

And of course, a pure screenshot result for the HWBot database:

Frankly speaking, it will be rather difficult to reach 40th place on the air. In my case, it is almost impossible. However, before I got my hands on the test specimen, it worked in terrible conditions, which adversely affected the physical properties of its crystals.

There is no question of stability here: at a frequency of 4617 MHz, the chip was barely able to pass validation in the CPU-z utility.

Overclocking settings for Pentium D 930 to 4350MHz:

- FSB — 290MHz;

- CPU multiplier — 15;

- FSB Voltage — 1.35v;

- CPU vCore — 1.348v (+0.187 volt to the base voltage)

- DRAM Clock — 580MHz (with a Pentium D chip installed, the board lacks a 533MHz divider, which makes it not the best choice for overclocking processors of this line);

- DRAM Timing — 5-5-5-15 2T;

- DRAM Voltage — 2.0v;

- PCI-e – 101MHz;

Test results

I think it’s not a secret for anyone that Pentium D series chips have been physically unable to run the vast majority of projects for several years now. The reason for this is the lack of the necessary instructions SSE4.1 and SSE4.2.

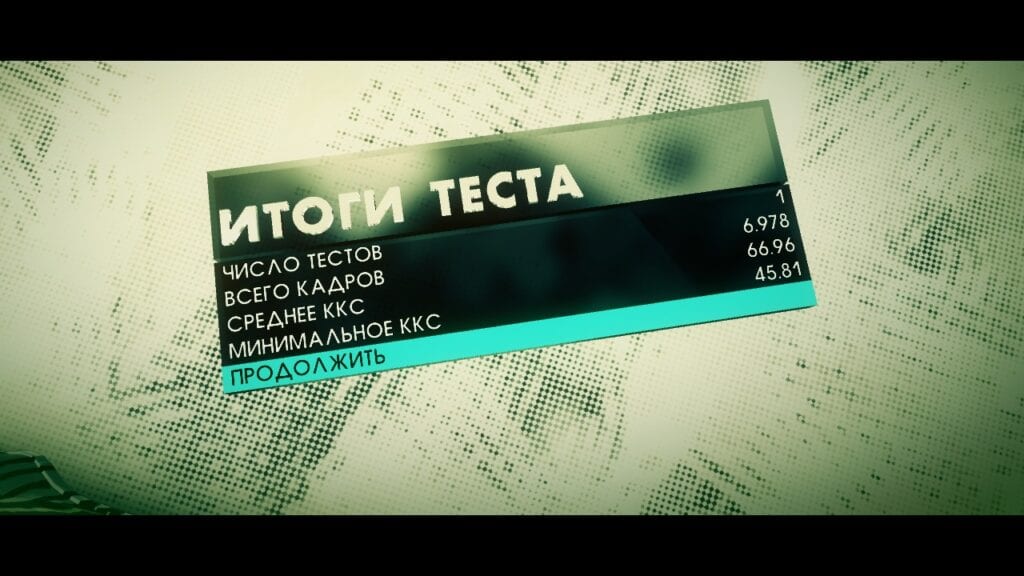

That is why I chose only one and rather old game DiRT 3 to assess the performance gain. This rally simulator was released back in 2011 and in theory (at least if you believe the minimum system requirements of the game), it should have run on an old Pentium D.

And so it happened, DiRT 3 launched, but I did not even suspect that on a 14-year-old processor, which even at the time of its release did not shine with a performance at all, it would be quite possible to play a 9-year-old project. Certainly not at maximum, and not even at medium settings, but damn it, play with comfort!

DiRT 3 used “Ultra Low” graphics settings and a resolution of 1280×720. The benchmark built into the game was chosen as a performance meter. The rest of the tests (Cinebench R11.5, Cinebench R15, and CPU-z Benchmark) were run with the basic settings of each of the programs.

Summary table with test results:

| Pentium D 930 processor frequency | 3000MHz | 4350MHz |

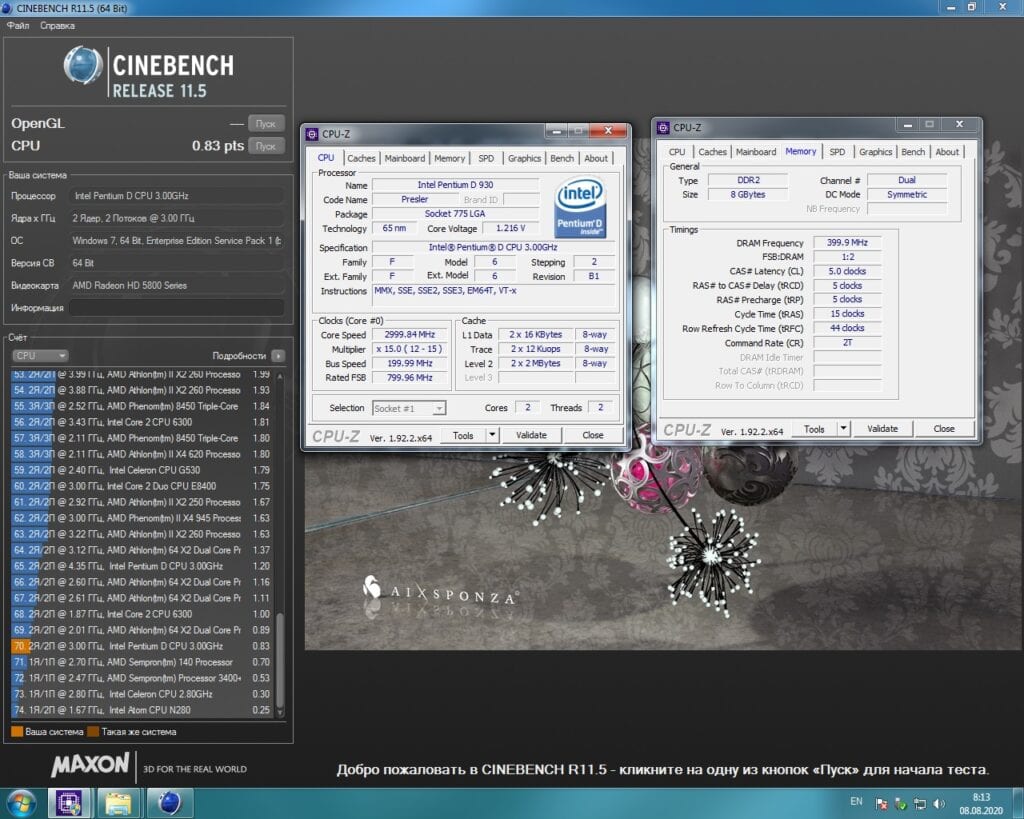

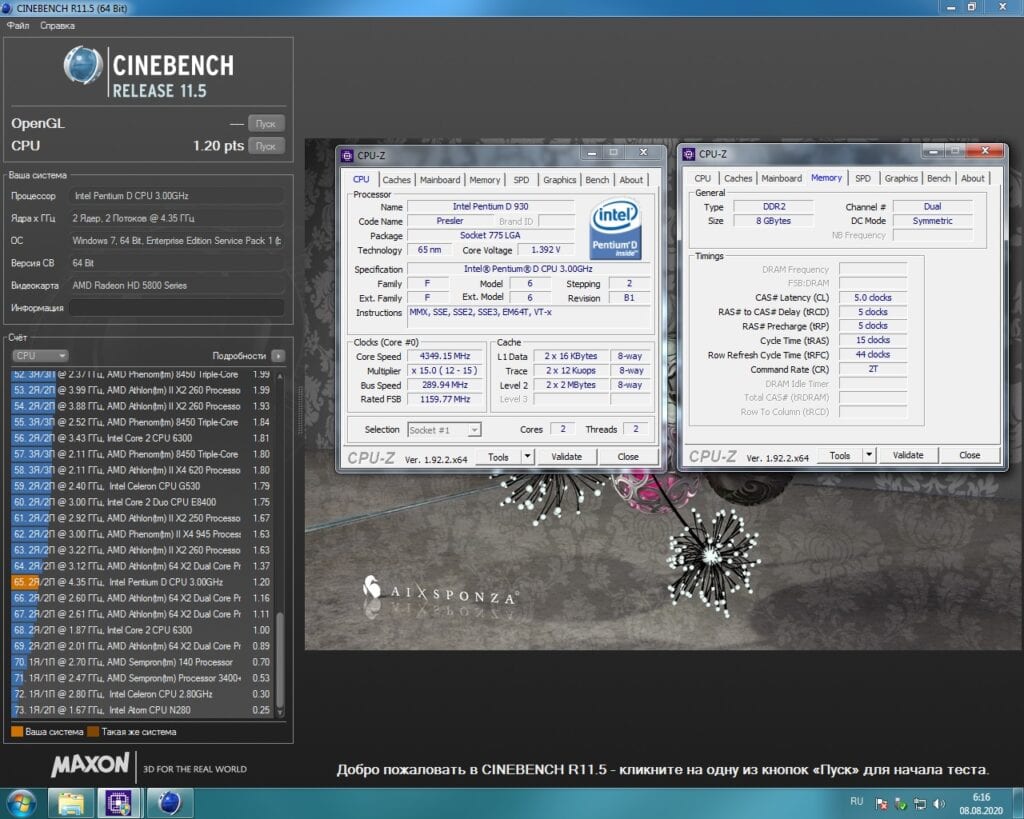

| Cinebench R11.5 results (points) | 0.83 | 1.2 |

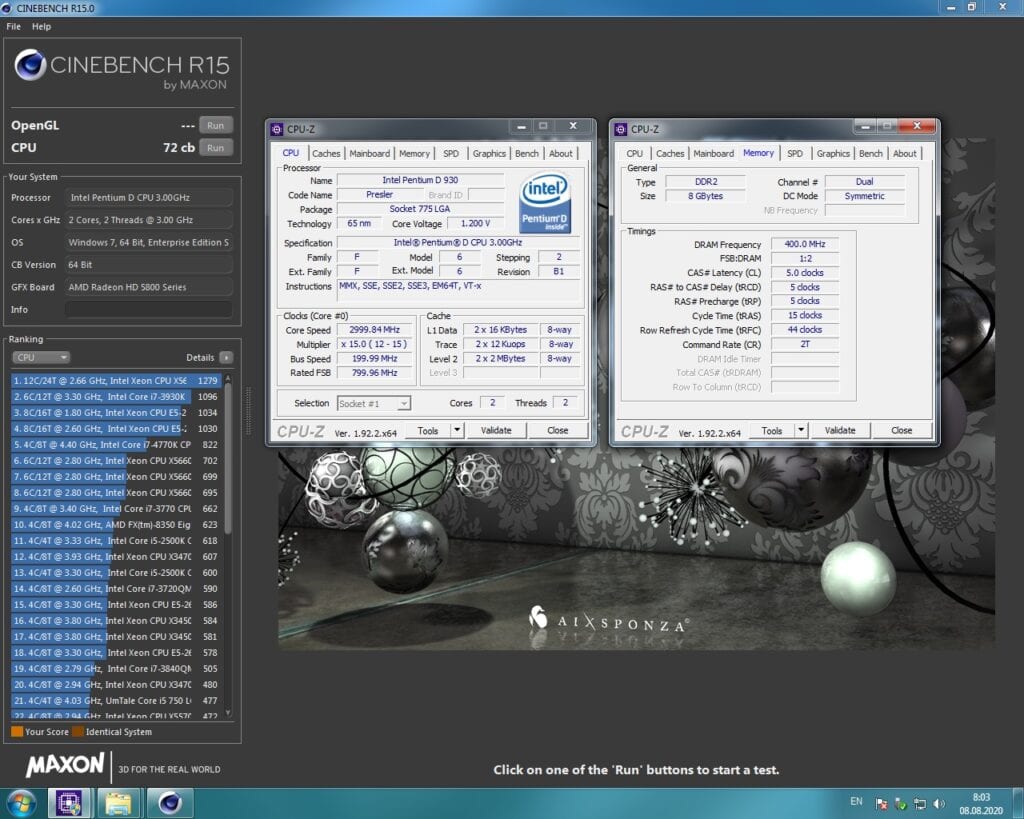

| Cinebench R15 results (points) | 72 | 101 |

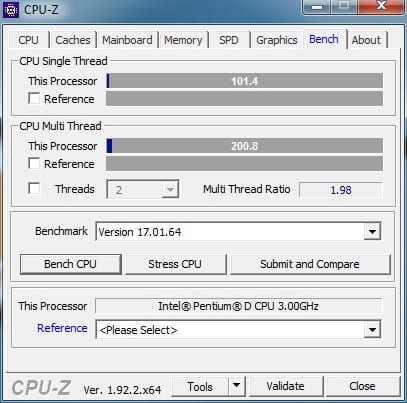

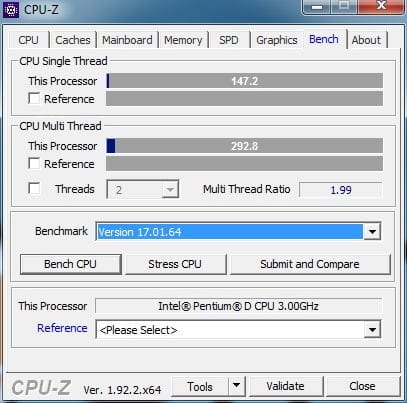

| CPU-z Benchmark results (Single|Multi) | 101.4|200.8 | 147.2|292.8 |

| DiRT 3 results (FPS – MIN|AVG) | 38|55 | 45|66 |

Benchmark screenshots:

The test results show that in synthetic benchmarks the performance of the Pentium D 930 overclocked to 4350 MHz increased by about 35-45%, depending on the program. But in the game DiRT 3, the situation is radically different. The increase in the frame rate was only 19% in the minimum indicator and by 20% in the average FPS.

And the reason for this was the rather mediocre frequency of the RAM and the FSB bus. After all, it is through it that the two crystals keep in touch with each other.

Conclusion

I still could not achieve the 5GHz coveted for the NetBurst architecture. And as you already read above, the reason for this was the insufficient cooling of the processor, as well as the extremely weak power subsystem on the bench motherboard. It is quite obvious that for extreme overclocking, 4600 MHz is a very, very weak result, which cannot be said about stable 4350 MHz everywhere. This result is already relatively good.

Nevertheless, I am perfectly aware that the copy of the Pentium D 930 chip available in our laboratory, to put it mildly, is not entirely successful and does not reflect the full picture of the overclocking potential of the Pentium D series of processors. Therefore, as soon as I get a few new samples of any representative 65nm Pentium family, I will immediately start examining their overclocking potential.

But in general, you should understand that virtually any Pentium D processor you buy in 2020 is likely to be in a terrible physical condition (crystal degradation, broken capacitors, and up to complete inoperability).

Happy overclocking!